- Home

- Larry Woiwode

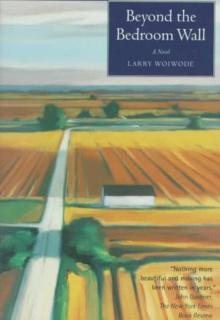

Beyond the Bedroom Wall Page 3

Beyond the Bedroom Wall Read online

Page 3

"I'm sure the missionary from Hankinson will come over."

"He's away to Fargo on a conference, starting today, and won't be back till the end of this week."

"Then a priest from Lidgerwood.”

"Charles, they're all gone off to Fargo, too, I'm afraid."

"Then maybe I'll have to bury him without a priest,” Charles said, and knew it was wrong to mention an idea so heretical to Clarence, who was a prude himself and a worse gossip than any number of women.

Clarence's face took on the blankness of a seasoned magistrate's, and then he winked his small eye and said, "Why not, Charles? And say, will you need help?"

"If you want, you can come out Thursday afternoon. I should be ready then."

"But that's tomorrow! That's a day and a half!”

"If I could do it today, I would."

"But what about the people that—"

A gray-and-tan nanny goat, a fixture in town for fifteen years, came around the corner of the depot and walked into the shade of the porch, its tapered hoofs tapping over the heavy planking ties. Then the goat drew up and regarded Charles with a coin-like, pragmatic eye, while its tiny jaws moved in a tidy munch. Charles turned and walked beyond its working beard, toward a road that crossed the rails at the other end of the station, and felt his intestines expand and slide over themselves inside him.

"You're not walking?" Clarence called to him.

"Yes."

"Surely somebody will give you a ride out?"

Charles walked on. The road, a dirt road that angled away from the edge of town, was dry and unshaded and soon he was in open countryside. The sun was rising, driving off the morning chill, and now and then a spout of wind would pick up dust from the road or a field bordering it and spin itself into oblivion in a few seconds. Otherwise, the day was still. Bird song, rising from the earth and different levels of the air, swayed and teetered on either side as though from a fixed point at the center of his hearing, a feeling he'd had before this, he felt. The road began to follow Sand Grass Creek, which was lined with low willows and cattails and dry saxifrage. The cattail heads were swollen and splitting, their silky seeds spilling from them, and in front of him, keeping a fixed distance, a red-winged blackbird went dipping from head to head as though stringing between them shining beads of its quicksilvery, reiterated song. The road turned. He stopped and shifted the carpetbag to his left hand. He could see, a mile and a half ahead, the stand of trees that marked his father's farm.

Otto Neumiller emigrated from Germany in 1881. "I was twenty-four then. The wind was so big the masts rocked down to the waves even full-trimmed." He bought a wagon and a team of oxen in Minneapolis and headed west. Even in the Old Country he'd heard of the virgin Dakota plain, as limitless as the sea to look upon— "And Otto knows the sea"—and with resources perhaps as infinite. "At first I didn't think there was such a place, seeing so much timber in Minnesota, but once I came across the Red River, I could feel the current of its waves." He entered a homesteading claim in the Dakota Territory in the spring, and sold the wagon and one of the oxen to buy a plow and supplies. Trees were so scarce there was no lumber for building, and what sometimes looked like trees in the distance were the last remnants of the buffalo herds moving off toward the Missouri. "Red deer and antelope were crisscrossing everywhere out there, too. I drove on out. The buffalo looked so big I was afraid to shoot the buggers. I hardly saw a one after that." He built his home-steading shack of sod. The first fall, his garden and twenty acres of wheat, which he planted by hand, went up in a prairie fire. His ox and his implements were lost. His shack would have burned, too, if he hadn't situated it in the curve of Sand Grass Creek, where it was all but encircled by water. "And the next year the hoppers came. The sky was so dark with them we had to light the lamps at midday. It was crops they got."

He was penniless, there were no neighbors, and he didn't trust himself to withstand the winter alone, so he went to family friends in Chicago and found a job as a drayman. At a neighborhood church he met Mary Reisling, an immigrant girl. "She was down there from Winona to work the winter, too." He married her in the spring and took her back to his homestead, and that year the crops bore, though battered by a bad hail, and he bought a milch cow and improved the shack so it was more livable. The following spring his first daughter, Lucy, was born. He planted poplars and maples and elms along Sand Grass Creek to serve as a windbreak. "When those trees began to grow, they were the only ones you could see for twenty-five miles, sir."

The railroad extended its line beyond Wahpeton, and it was possible to buy lumber from the East. He built a twelve-stanchion barn and began work on a house. The crops that season were the best they'd been in a decade— a windfall, a bounty, and he opened his first bank account in America. Another daughter, Augustina, was born. He took on a hired man and broke up twice as much acreage, and again there was a windfall. He finished the house, two stories with four bedrooms, and bought a dozen head of Hereford and a hundred sheep. That year North Dakota entered the Union and I became a citizen of the U.S. of A." He began to acquire bordering farms that had been abandoned, and by the time his son was born, in 1891, he was the most prosperous landowner in the area.

"If I had a son, I always said I'd name him Charles after his Grandpa Neumiller, and John after his grandpa on Ma's side. But he came on Christmas Day, so I added on Christopher. I walked to Wahpeton to get the doctor and the snow was so deep the doc had to drive his buggy down the tracks, opened by the train, and wouldn't trust his old mare to get us both there, so I walked all the way back, too, and the boy was born when I got here."

He was a shrewd but simple man, embarrassed by his German accent, he cared so much for this country, and what he mostly wanted to do was please; he was of the generation old enough to see, from the knife point of 1900, equally well into either century, and see at a look what might last.

Against the advice of everybody he knew, he put in two hundred acres of corn, a crop that hadn't ever been raised in the state, except by the Mandan Indians, and it was a success. He bought another section of land. Mahomet was going up at the junction of the Great Northern and the Minneapolis, St. Paul & Sault Sainte Marie lines, and he made some sound investments in the first businesses there. "Then Lucy married below herself, to a cattle buyer, and they went to live near Fergus Falls." When contributions were being solicited to build a Catholic church, he donated fifteen hundred dollars to the fund. On Charles's twenty-first birthday, he took Charles aside, handed him a bankbook, and said, "This is one quarter yours." There was ninety thousand dollars in the account. "The Neumillers have always been took, my dad used to say to me, but this is one that ain't going to be, Charles."

In 1915, he built a large house in town, said he was retiring, and gave his farm to Charles. In town he was elected county commissioner and appointed to the school board, and when a group of farmers started a co-op elevator, he invested in it, and persuaded business friends to do the same. The farmers were uneducated and suspicious of strangers, and naive about financial matters, and the man they hired to manage the co-op, being one of them, was mistrustful of Easterners and got taken in by some buyers from St. Paul, who bought from him below market price, promising bonuses to the co-op at the end of the year for volume, and then reneged. After which the manager became so cautious he failed to sell when he should have, and then had to sell at a loss. The elevator went heavily into debt. Otto Neumiller was elected to the board of directors in 1927, and two years later the Crash came.

He lost thousands in the grain market, but was the only member of the board of directors who remained solvent, and when this was discovered bill collectors came to him. "I felt responsible for the man we had there and the losses my friends took." He raised enough cash to keep the co-op from closing, but in doing so had to sell his house in town and all the land except the eighty acres he'd originally homesteaded, and would have sold this, too, but the property was in both his and his wife's name, and she refused to sign t

he papers. "We argued about it all through the night, and when I woke the next day the papers was gone." Co-ops were closing all over the state, but as long as the one in Mahomet stayed open he never doubted he'd be repaid. "I figured if we could keep this one open we'd make acres of money." When it closed, he and his wife moved back to the home place, and Charles moved his family to a farm forty miles away, near Courtenay-Wimbledon.

Everybody in Mahomet knew that Otto Neumiller's farm wasn't under mortgage, as theirs were, and imagined he had money hidden away while their children went hungry and in rags. "And I did walk around with a shovel for a while, looking for those papers that had been hid." He raised a little grain each year and kept himself and his family in food, and not much more. There was no way of explaining that this was the way things were. People had stopped visiting him and inviting him over, and in town they crossed the street to avoid him, and even moved out of the vestibule of the church when he stepped in. He felt guilty about the wealth he'd once had and went to closing auctions and bought articles he didn't need and let them stand on the grounds for others to take.

His wife died. He became dazed and slovenly about his health, and began drinking too much. His wife had signed her share of the farm over to Augustina, who'd never married, and Augustina stayed on and tried to care for him. He'd go for days without eating, and reverted to speaking German. He and Clarence brewed beer in the basement and sat up at night drinking and playing cards. He was old, his heart was bad, he'd always been a heavy drinker, and the daily drinking added to his general decline. He let his fields go to pasture, to weeds and pocket gophers, and kept only the garden. And now he was dead. And for Charles it was merely a matter of time.

He stopped at the mailbox. There was nothing in it. "Bills are the ones with windows in them," his father often said. Otto Neumiller was painted across the box in an ornate Old World script, in bright orange paint. "If you're

going to do a job, do it right" sounded in Charles's ears, as though his father had spoken at his side this time. His father loved work brought to completion well, to the point of perfection, if possible; the care he lavished on the simplest tasks and his exuberance as he worked, small and elflike, smiling, wide-eyed, winking and asking you to come and see, as innocent of his pride as a child. Every spring he retraced his name on the mailbox with new paint. His hand was still steady.

Charles stepped back. The pole of the mailbox had been struck and knocked aslant by a piece of pulled machinery or a passing car. He put his carpetbag down and shoved and tugged at the box, trying to loosen it, then went down on one knee and drove his shoulder against the pole. It hardly budged. He threw his weight against the pole again and again as he pivoted around it, driving packed earth away from its base in a widening ring, and at last, shaking and lifting at the same time, pulled it free. He was flushed and fighting for breath. He held it at the top, close to the box, picked up his carpetbag, went down the lane to the house, and propped the mailbox against the chimney, near the porch.

Augustina opened the screen door and came onto the porch. Her gray eyes, magnified by glasses, were fearful and apologetic, and she was twisting a handkerchief at her waist. She raised a hand as if to speak, and then clamped her lips tight and her eyelids closed. Her forehead was higher than his, and her eyebrows thick and mannish. The handkerchief looked ragged, her dark dress was worn and dingy, and her hair, once a reddish aureole around her face was tan-gray and drawn into a frizzy bun. He was hurt by how she'd aged, and by her lack of concern about her appearance. He stepped onto the porch and took her in his arms.

"Charles. Thank God."

Her body beneath the dress was surprisingly feminine, frail yet full, her breasts large and firm against him, and he realized how easily she could have married. Had she remained single out of fear—since adolescence she'd been high-strung and terrified of strangers and subject to "spells" —or was it simple devotion to their father? For her devotion to him was always overabundant and colored with a childlike awe.

“I thought I wouldn't be able to bear waiting or keep myself sane," she said. "I haven't slept since he died."

"How was the end?"

"It was as if— He'd been feeling all right and I brought him— Come inside. Please."

They went into the parlor, bare except for a faded carpet, a long oak table, and a horsehair sofa, and before Charles could adjust to the room her arms were around his neck and he felt through his shirt the dampness and heat of her tears. He eased the carpetbag to the floor and pressed her head to his shoulder. "Here," he said. "Here now."

"I feel so sick and ashamed!" she cried.

"Why?"

"I helped the doctor lay him out and haven't gone near the room since."

"Why should you?"

"I feel he's still alive."

"That's foolishness."

"I can't help it, I feel it! I can't sleep, I can't eat, I feel sinful and sick and that I'll never be the same from not seeing if he needed me."

"What could you do?"

"Talk to him?"

"Ach!" Spiritualism irritated him more than anything he could think of, and he was surprised that Augustina had let herself be taken in by it. "What did the doctor say?"

"What did he say?"

"What was the cause?"

"His heart, he thinks."

"He wasn't sure'"

"No. He's so restless!”

"Old Doc Jonas?"

"Dad!"

"Augustina, please. Be reasonable. He's at peace now."

"I can't even pray."

"You will."

"I hate too much."

"Hate?"

"How can I help it? They've already been out. They heard he died and they've been carting off machinery and grain, and Frank Kubitz even took the team of bays. His only—" She swayed as though off balance and held him tighter.

"That'll stop."

"They tell me it's owed to them and I tell them to wait, at least till you're here, but they won't listen! They just walk off with what they want."

"Everybody thinks they're owed something when they're poor."

"We're poor. He was."

"I know, I know, but they don't."

"Make them understand!"

"I will."

She drew away and wiped her cheeks with the handkerchief, wiped under her glasses, and then across her high forehead. "I’m sorry," she murmured. Her eyes were depthless with a feeling he couldn't define. "I've never been alone before. I'm so thankful you're here. How are Marie and the children?"

"Fine."

"And you?"

"As well as can be."

"I understand," she said.

"How was the end?"

"I brought him breakfast and he seemed in good spirits, he talked and laughed, and when I looked in to see how he was doing, he had a piece of toast in his hand and was staring straight ahead—thinking about something, I thought—so I let him be. He's been reliving so much of his past life since spring. But when I went back a while later, he was in the same attitude. He died that way."

Charles went across the parlor and opened a door. The curtains of the room were drawn, the air dim and gold-colored, and on the high bed with its carved-oak headboard he saw the outline of his father's body beneath a sheet. He stepped inside and closed the door behind him. He dipped his fingers into a font of holy water fastened to the molding of the jamb and made a sign of the cross, and then turned back the sheet to his father's shoulders; thick silver hair rayed upward over the pillow, giving his face an unprotected look, lips dark and parted, and the white scar across the bridge of his nose violet A scar from a fight. When had it happened? Why? The lid of his left eye was halfway open, and a clouded iris showed. Charles closed the lid with his thumb, but it slowly retracted, and was once more open on him.

In the top drawer of his father's bureau he found a leather change purse, took two silver dollars from it, pressed the eyelid down, and placed the coins over it. He snapped the purse shut and

held it, trembling. His father's beard, shorter and thinner than he remembered, flared up from his lifted chin like a silken brush. With his fingers Charles stroked the beard smooth, the way he'd seen his father stroke it from the time he could remember.

God rest you, Father.

He drew the sheet back over his father's face as he'd found it, crossed himself again, left the room, and sat at the oak table in the parlor. He pressed his fingers against his eyelids, which were stiff and felt thickened and numb, and the pain in his head suddenly brightened and went spiraling deeper until he wanted to cry out. He said, "Did Dad receive extreme unction?"

"Several times."

"Has a priest been out recently?"

"Two days before he passed on."

"Did Dad receive it then?"

"Yes. He asked to."

He uncovered his eyes and looked up. "There might not be a priest to say a Requiem."

"I know. There's a conference in Fargo."

"Does it bother you if there isn't a Requiem?"

"I haven't felt we've had a priest in town since Father Meyer left," Augustina said. "And neither did Dad."

Charles took his suit and white shirt from the carpetbag and went to the foot of the stairs, where coat hangers hung from wooden dowels.

"I suppose we'll have to sell out," Augustina said, and he turned. Her eyes were plaintive and tearful, and she was twisting the handkerchief again. "And what will I do then? Could I come live with you and Marie? I could help with the children. I can still do chores."

Charles finished hanging up his clothes. “We'll talk about it later," he said. "I have to rest. You should rest, too."

He went over to the horsehair sofa and, before he was aware of striking its leather cushion, was asleep.

In his dream the German word best had a new significance: now it was a homonym of "beast" and a synonym of it, too, and it applied to him, because he'd been deformed. He was lying on his back in a meadow smaller than his body when a horse mower came toward the best (beast) part of the meadow and mowed his hands off as cleanly as hay.

Beyond the Bedroom Wall

Beyond the Bedroom Wall